Congrats to Precision MMA’s Dan Power and Paul Maley for their victories at the upstate Golden Gloves! They now advanced in the tournament, as they hope to join Precision’s Coach Derrick and Pat Daka as golden gloves champions!

The coaches at Precision MMA are always striving to learn from the best and better themselves as martial artists. Coach Brian and Stanley traveled to Virginia to learn from one of the best BJJ Black Belts in the US, Ryan Hall. Read about their experience HERE

Great techniques from my friend Matt Arroyo

http://www.bjj.org/open-guard-vs-standing-opponent-tampa-bjj

Check out the “ninja roll” back take shown by head coach Brian McLaughlin

Click HERE for the technique

Coach Brian talks about his experience with this often dangerous practice HERE

Here’s a killer way to avoid the triangle choke from my MMA Tampa friend Matt Arroyo

http://www.bjj.org/the-magic-grip-triangle-defense-mma-tampa-technique

In the early days of The Ultimate Fighting Championship and throughout the 1990s and even the early 2000s, MMA fights were generally seen as “style vs style”. I remember being thirteen years old and getting the Pay Per View flyer in mail for UFC 1 which read “Jiu-Jitsu vs Savate vs Tae Kwon Do vs Boxing vs Draka vs Kickboxing vs Shootfighting vs Sumo Wrestling” (I wish I had saved it be honest…). At the time I was a Karate practitioner and this theme of pitting different styles against each other to be fascinating and was instantly intrigued and the rest, as they say, is history. The same has happened to a large extent in the world of competitive grappling: wrestlers will enter Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu tournaments and often blow through the competition with just a little bit of BJJ training and claim that their “wrestling” is what won them the match, ignoring the few essential BJJ techniques they needed to know to win.

Likewise, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu competitors will utilize double and single leg takedowns to win a tournament match but still claim it was only their Jiu-Jitsu which won them the match. In the end, most if not all of these distinctions are pointless, and in fact, they are often quite harmful. It is one thing to acknowledge that certain strategies or methodologies are separate among different grappling styles. For example, a wrestler wants to be on top at all times and will not place much emphasis on passing guard because in his sport that is not a necessity. A Jiu-Jitsu practitioner will emphasize the strategy of having an active guard or passing to sidemount because it scores him point in competition or a Judoka may stress throwing ones’ opponent perfectly head over heels without following them to the ground because this scores points in a Judo contest. All these distinctions in terms of strategies are fine in my opinion, and separate classes teaching these differing strategies can be helpful. What is harmful in my opinion is when one martial arts’ school refuses to teach or incorporate styles from another discipline in order to be able to say they are “purists”.

In my opinion the underlying reason behind why so many martial arts schools refuse to incorporate techniques from other styles is their vested interest in proving that “their style is the best”, and often this also comes down to name brand value and monetary gains. In the end however, this hurts the students who do not, for example, get to learn valuable takedowns from wrestling in their Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu classes because the instructor wants to stay “true” to his art. With the growth of popularity in Mixed Martial Arts some of this has changed. There are many MMA fighters who are excellent at Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and wrestling for example, who never took a formal Jiu-Jitsu class or wrestled on a wrestling team. If asked what their “style” is, they will simply say “MMA”. This is quite similar to the idea that Bruce Lee had behind his “art” of Jeet Kune Do. He has been quoted as saying “my style is no style”. He realized that the division between arts was largely harmful and simply taught what was useful and discarded what was not. In my opinion, though we have come a long way with the growth of Mixed Martial Arts and submission grappling, we have not come far enough in terms of integrating the different grappling styles of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, Judo and Folkstyle, Freestyle and Greco-Roman Wrestling. Still to this day many claim “wrestling is the best base as a grappling style for Mixed Martial Arts”, and whether or not this is true, if it is indeed the case it is in my opinion because other grappling arts like Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and Judo have failed to incorporate enough wrestling techniques in their training, while wrestlers have not failed to do the opposite and are not shy about learning Jiu-Jitsu and Judo if necessary. There are many other ways in which I think “the battle of the arts” has hurt Martial Arts practitioners as a whole, and in particular, the ability for Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu practitioners to learn high level takedowns has been hindered. In this article I will explain a number of actions that I feel can be taken to make the grappling styles of Wrestling, Judo and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu more integrated, particularly in regard to their takedowns.

One of the biggest problems that I see in integrating grappling styles like Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, Judo and Wrestling is that seeking instruction in these arts seems to be a uniquely different process for each and coaching in these styles cannot usually be found under the same roof. For example, when I was growing up I exclusively attended small private schools which did not have wrestling teams. Despite the fact that I always wanted to learn to wrestle, this was an impossibility for me until only several years ago when my current school of Precision MMA in Poughkeepise, New York started bringing in wrestlers to instruct us in takedowns. Though I looked high and low, it was extremely hard for me to find clubs that would instruct someone in wrestling if that person had no wrestling background. While I did eventually start to locate certain clubs, like the now defunct “Wrestlers Come Alive” club which was run by Eric Amato and Ian Lindars in Hopewell Junction, New York, I saw a problem there that I had become aware of when calling around for wrestling clubs as an adult. I would call a wrestling club I found online and the coach on the other end of the phone would reply “yes, we instruct people in wrestling, but 90% of our students are children and early teens.” And so as an adult going there did not seem an option to me. Therefore, one way that I propose to make wrestling more available to the general public is to increase the number of both child and adult wrestling clubs. With the growth of MMA there should be no shortage of people looking for paid instruction in wrestling who never wrestled in school, and it would be a great opportunity for those kids who’s schools do not have wrestling teams to learn to wrestle this way.

Another idea I propose is one that I have mentioned and heard opposition too, and this is the idea of offering Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and Judo teams in schools as an afterschool sport just like wrestling is. The current format between these arts seems to be that if one wants to learn to wrestle then they will need to learn it in school and hope their school has a team, and if they want to learn Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu or Judo they will have to pay to attend a dojo which teaches these arts. Therefore, many who take up wrestling in their school systems for no extra cost may not get the chance to train in these other arts, just as those who train in BJJ or Judo will not learn to wrestle if their schools do not have a team. I therefore propose that both public and private elementary, high schools and colleges should offer after school programs in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and Judo for no additional fee. Students should compete to make the “Jiu-Jitsu team” or “Judo team” just as they currently do with wrestling and the idea of schools having Division One or Division Two Jiu-Jitsu practitioners should become a reality. This idea often meets with opposition because people say that Jiu-Jitsu is too violent an art for schools and that parents would not be willing to enroll their kids. Yet Football is a sport offered in nearly everyschool and produces countless concussions and even a few deaths per year so I fail to see this as valid point. If, however, a school system is too concerned with the danger of the joint locks practiced in Jiu-Jitsu or Judo the least they could do is offer a modified form of these styles allowed chokes as the only legal submission. Despite popular belief, BJJ and Judo choking techniques are extremely safe and easy to practice at full capacity in competitions without causing injuries.

One avenue by which the takedowns taught in Wrestling and Judo could become more integrated into Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu is already being employed, and that is to offer more “takedown divisions” at Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu tournaments, whether they be done in a No-Gi or Gi format (and I propose more grappling tournaments should offer both though I have never seen a “gi takedown division” offered at a BJJ tournament). I have been lucky enough to take part in a few no-gi “takedown divisions” at Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu tournaments over the past few years and they are a great deal of fun. However, I still feel that not enough Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu tournaments offer them, and not only that, but I think that promoters should create entirely separate “takedown tournaments”, which have neither Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, Wrestling or Judo as their focus, but simply students of all styles who wish to test their takedown skills against others. This would offer an excellent avenue for wrestlers, Judokas and Jiu-Jitsu practitioners to work even more on the takedowns which are so essential in all these grappling arts and especially modern Mixed Martial Arts. Afterall, while many of the takedowns used in these tournaments might originate from wrestling, much of the mat game in wrestling is entirely inapplicable to Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, Judo or Mixed Martial Arts so even if a student of these other arts were to enter a wrestling tournament they would only be getting so much out of it because the second they hit the ground with their opponent they would be forced to play a game that has no value to them. As such, even if they do have the opportunity, many Jiu-Jitsu and Judo practitioners would never enter a wrestling tournament despite the valuable experience it would give them in takedown offense and defense.

Though I will only briefly mention the following idea, because it might take us too far off course, I myself have a growing fascination with the separate art of Catch-As-Catch-Can Wrestling and would like to see the art spread and see more CACC schools and tournaments pop up in the near future. Indeed, this ancient sport where opponents can win either via pin or submission has been experiencing a revival of late and there are a few CACC dojos and tournaments offered in the North East U.S. for example, but not enough in my opinion. A resurgence in this art and it’s training methodologies could only help wrestlers, Jiu-Jitsukas and Judokas as I think it potentially has some valuable techniques and strategies to offer. If this art does begin to grow I also think some of its techniques should be taught at Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and Judo schools and maybe even by wrestling coaches who want to think outside the box while training students in after school programs.

This next idea for how takedowns across styles can become more integrated into each other is certainly going to meet with a lot of criticism in the Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu community, and yet I feel strongly about it so I am going to mention it anyway. As can be seen, many if not most of the points I have been making relate to more integration of the takedowns from different grappling arts more so than the mat game. The reason for this is that the art in which I personally have trained the longest in, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, so frequently neglects takedowns while most other grappling styles do not, and this I find very unfortunate. All styles of wrestling, Judo and Sambo very highly stress takedowns, and yet BJJ is the one grappling art where someone can not only get by, but actually rise to the top of the sport without having nearly any takedown abilities whatsoever. And yet, when these Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu practitioners cross over into Mixed Martial Arts and lose to those with wrestling backgrounds because they cannot get top position or even get the fight to the ground, they not only wonder why, but many of them are too proud to even cross train in wrestling because they consider themselves “Jiu-Jitsu purists”. This is unfortunately especially the case with those Jiu-Jitsu practitioners who originate from Brazil because wrestling is very scarce down there while it is very popular in the United States. For those reasons I propose that Brazil, just like the U.S. and the rest of the world, should have more wrestling teams, more wrestling clubs, and more Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu schools which incorporate wrestling. But aside from that, Jiu-Jitsu practitioners of all backgrounds are far too willing to drop to their backs and pull guard in BJJ and submission grappling tournaments.

Now, while there are a number of popular BJJ tournaments world wide that will likely not be changing their rules any time soon, new promoters and promotions are popping up at all times and there is certainly room for more grappling and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu tournaments with unorthodox rule sets. I propose that some grappling promoter with the means to do so creates his own promotion under which guard pulling is either not allowed for the competitors, or if it is allowed it should cost the competitor who drops to bottom guard the points that he would lose if taken down by his opponent. While many Jiu-Jitsu purists would be up in arms about such an idea because pulling guard has become so popular in BJJ, to them I would ask the question “how much better do you think you might be at takedowns if guard pulling was not a legal tactic in Jiu-Jitsu tournaments?” None of them would be able to deny that they would have developed better takedowns if guard pulling were not an option and none of them could reasonably deny that takedowns are an essential skill for all styles of grappling and MMA. I myself have competed in 34 separate Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and grappling tournaments and I know for a fact that if guard pulling had never been an option for me today I would have ten times the takedown ability that I currently have out of necessity. At the very least, if guard pulling were to cost the Jiu-Jitsu practitioner the points that would normally be awarded his opponent for the takedown (which is two points under most tournament formats) he would have to admit that if he was highly opposed to this idea he must not be extremely confident in his offensive guard abilities in the first place or else this would be of little concern to him because he would be confident that he would win regardless.

In my opinion, competitive Jiu-Jitsu has far too much butt-scooting and guard pulling for its own good and has in many cases evolved in the wrong direction. Certain tournaments have rules where a grappler can simply touch his opponent and then sit to his butt and the other grappler must immediately engage guard. Other tournaments have seen the growth of the “double guard pulling” tactic in cases where neither competitor has any takedown skills. All these practices move Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu further and further away from its original aim as a true all around fighting art. The only point to which I will concede is that if a tournament’s rules are to prohibit or penalize guard pulling that the opponent on top should not be permitted to back out of guard once the match has landed there, because this would be considered unwillingness to engage.

In fact, I am not the only one who would like to see Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and submission grappling return to their roots and this is why more “submission only” tournaments like Metamoris and others have begun to become popular. I think this is great and that the more of them exist the better because grapplers will become less focused on arguing over “which style is best” and more focused on doing whatever it takes to win.

The final main point that I will make in this article is that more Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, martial arts and grappling schools need to teach multiple styles of grappling and highly stress takedowns if they are to compete with the growing number of wrestlers competing in both grappling tournaments and Mixed Martial Arts. In fact, even if one has no aspirations of competing but instead trains for self-defense, if he is training in a grappling art, he needs to be learning takedowns because otherwise the fight will never hit the ground. As my Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu instructor Brian McLaughlin has stated “knowing Jiu-Jitsu without knowing takedowns is like having a gun without bullets” and I agree with him completely. All the chokes and joint locks in the world will not make any difference if the grappler can never take his opponent down since most of them cannot be applied standing. This is why my current training facility of Precision MMA in LaGrange, New York includes a heavy emphasis on takedowns. Almost all of our training sessions begin from the feet unless we doing a particular ground based drill and our no-gi classes have wrestling coaches Ian Lindars and Dan Sanchez to instruct us in takedowns from that style while our Gi classes have Judo black belt Jerry Fokas give us his input regarding the Judo style takedowns necessary for success in Gi competition. Not only this, but in certain cases head instructor Brian McLaughlin will show no-gi applications for Judo throws which are slightly different from their wrestling counterparts, and to show that we are truly open minded in our mat game as well, coach Karl Nemeth often includes leg lock techniques from Russian Sambo in our no-gi classes.

In a perfect world, all grappling styles, be they wrestling, Judo, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu or Sambo would be offered in as many settings as possible: in after school programs and on scholastic teams, in dojos, and even the Olympics. Indeed, it is quite unfortunate that wrestling has been taken out of the Olympics and is now being offered in fewer highschools and universities. Not only would I like to see wrestling back in the Olympics, but I would also like to see Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, Submission Grappling and Sambo become Olympic sports and I would like to see a revival in more paid wrestling tournaments like the now defunct “Real Pro Wrestling”. I even mentioned in a past article that I think Gi MMA promotions would enhance more Mixed Martial Artists’ knowledge of Judo and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. All of these things would help produce an overall integration of grappling styles which would bring about the highest possible percentage of top notch-well rounded grapplers world-wide. Mixed Martial Arts has certainly begun to pave the way for Bruce Lee’s vision of “all arts being one”, but we have much more work to do if we are truly to see this vision become a reality. I am not saying there should not be separate classes and tournaments for separate grappling arts or that the rich time honored traditions of these styles should be forgotten, I am merely saying that these styles can survive while at the same time becoming more fully integrated with and less opposed to other styles which can benefit them.

This, my friends, is the way of the future. The martial arts’ world is like a jungle and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, as well as Judo, Wrestling and other grappling styles, are in a position where they must adapt our die. If we are too proud to teach or learn techniques from other styles because we wish to be “loyal” to our core art, then we will lose in competition to those who are more open minded, and this is especially the case if we do not heavily focus on takedowns in all our classes. At the end of the day, it really doesn’t matter whether we call a double leg takedown a “wrestling move” or a triangle choke a “Jiu-Jitsu move”, all that matters is that we practice it if it is effective. Hopefully the day will come when all grappling styles are so integrated that these distinctions are meaningless and we can focus on the task at hand, which is producing excellent all around grapplers.

Jamey Bazes is a Poughkeepsie Mixed Martial Arts practitioner holding a Tampa Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu brown belt with over 15 years of competition experience earning over 100 tournament victories. He also holds a Masters of Arts Degree in English from SUNY New Paltz with a focus on the English Romantic poets.

When one seriously devotes oneself to the practice of martial arts injuries are simply an inevitability. It isn’t if they will occur but rather when and what type they will be. They must be considered an occupational hazard and in a sense, a rite of passage. You know someone is truly serious about the martial arts and considers it more than a minor hobby if they can endure a serious injury, go through surgery and months of physical rehabilitation and still return to train again. Nobody wants to get injured, but if you train hard enough and long enough the odds are against you never having anything go wrong. As they would say in Buddhism, all things are impermanent and all things break down, especially the body. However, if one mentally prepares for this ahead of time it will greatly enhance their ability to make the best of these set backs. As the old saying goes “if you’ve got lemons, make lemonade”. The practice of the martial arts makes people both physically and psychologically stronger, and that goes for injuries in addition to victories and defeats in the ring or on the mat. In this article I will discuss my own personal experiences with injuries in the martial arts and how I believe they have made me a better martial artist while also using examples of other martial artists who have physical limitations but have still thrived nevertheless.

When I first began training in the art of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu at age 16 I was not of the mindset that I would ever get injured. It was not until I was in my mid 20s and began training with serious Pro MMA fighters and grapplers and heard about their injuries that I realized I would most likely have an injury at some point. My first serious injury occurred when I was twenty-eight years old. While practicing Judo throws with my instructor I attempted to base out with my right leg in order to defend against the takedown. I had not yet learned Judo break falls, which I have since learned, and did not at the time realize the mistake I was making. My knee twisted sideways and popped, and as I went down in pain I knew that something serious had just occurred. Soon afterwards an MRI confirmed that I had in fact torn my right anterior cruciate ligament, which is one of, if not the single most common injury throughout all sports including martial arts. Before this first knee surgery I had quite a bit of trepidation. I was not sure how I would recover and whether or not I would be able to go back to Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu feeling the same as I had before. I had never gone through physical therapy and was not looking forward to all the pain I would have to endure. I had heard that other people who had torn their ACLs had not been able to recover fully and had not gone back to training in the martial arts. However, I also knew that my instructor, Brian McLaughlin of Precision MMA in Poughkeepsie, had also torn his ACL and had returned to become better than ever before and become a well-known MMA champion in the Hudson Valley area and throughout the Northeast United States. This gave me hope that perhaps I too could come back in one piece from my surgery.

After I awoke from my knee scope my first few weeks of rehab were a rude awakening. One of the first exercises I remember having to practice was simply to sit up-right in a chair with my back flat against the backboard and to try to lift the bent injured knee to my chest. To my dismay, on my first try not only could I not lift my knee to my chest, I barely even had the strength to lift my foot more than an inch off the floor. Quite frankly, it was shocking. A movement that I’d been able to do since I was a toddler was completely impossible for me, and took weeks of daily practice to be able to perform again, and with every attempt I would experience quite a bit of pain. This was just one of so many normal movements I could not perform. I could not walk without crutches and I could not even stand up fully without leaning on something. After about a month of rigorous physical therapy however, I found that I could very carefully walk a few steps without crutches, and when I achieved it, it was a major breakthrough. After about 2 months of rehab I was able to balance on the injured leg itself for up to 40 seconds, and only someone who has been through a surgery like this can understand how that can feel like a major accomplishment. Soon I could walk without crutches, then walking progressed to jogging and finally jogging progressed to running. Before I knew it I was back on the mat doing Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, Muay Thai, wrestling and boxing just like before. However, this was not the last injury I would have to endure. My rites of passage were not over yet.

At age 31 I was doing some no-gi grappling in a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu class with a newer student and when I tried to take his back he attempted some sort of escape which left me off balance. I fell to my left side and my left leg twisted underneath me and popped loudly, just like the right one had two and half years earlier. The second that I felt my knee buckle I immediately knew that I had injured my left knee in exactly the same way as the right, and an MRI confirmed that this time not only had I torn my left ACL but I had also partially torn my MCL. When I went through rehab this time my mind felt pulled in two directions in terms my thinking about my recovery. On the one hand, I had been through this before and so I was overall much more optimistic than the first time. I knew what knee rehabilitation was all about, I wasn’t entering the unknown and I knew very well that I was capable of fully recovering and would not be surprised by any of the difficulties I would encounter. However, I also knew that this time upon returning I would have two surgically repaired knees. I was not sure how this would impact me and whether or not I might have been overly relying on the left one last time. Yet my experience with the first injury proved invaluable as I recovered in record time from this injury with much less trouble than the first. In fact, I believe that now both of my knees and legs in general are physically stronger than they ever were before due to all the rehab I went through. Before I even returned to BJJ after the second knee surgery I was leg pressing 450lbs with only my left “injured” leg, and experienced quite an ego boost when I would see other people attempt to press that same amount of weight with both of their uninjured legs, and fail. It was at this point that I realized for the first time in my life that I was capable of running a sub seven-minute mile, and that I could keep up a pace of 10 miles per hour on a treadmill for two minutes straight despite being slightly overweight. All the rehab had improved my leg strength beyond what it had ever been before.

When I returned to Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and martial arts at Precision MMA this time I noticed a number of differences begin to evolve in my game. First of all, because my left knee was sensitive to base out on from where the incision had been made I found myself basing out on my left foot while passing my opponent’s guard and improved at this sort of passing, and I also began to improve some of my standing guard passes as well. Once I had passed my opponent’s guard I found myself more likely to place my left knee on the opponent’s belly and became much better at holding this position as a result of the knee being too sensitive to put directly down on the mat, and I also started working more on my kasagatomi position rather than normal side control where the knee would be driving into the ground. While doing takedowns I stressed those moves which would not involve my left knee touching the mat to avoid the discomfort, and in some cases I worked on takedowns where neither knee would touch the mat and became better at these sorts of takedowns overall. It is also important to note that the practice of not allowing your knees to touch the mat for long periods of time while doing takedowns or while ground grappling is an important skill to learn for street self defense since even an uninjured knee will hurt quite a bit if grinding against hard pavement.

One other major area of my game that I improved as a result of my left knee having recently been operated on was that I started to move away from doing so many leg locks in my regular Jiu-Jitsu training. Leg locks have always been one of my favorite attacks in grappling but one problem with them is that when going for a leg lock one often leaves oneself vulnerable to the leg locks of the opponent. Despite the fact that according to my orthopedic surgeon a repaired ACL with patella tendon graft is roughly 27% stronger than a normal ACL, I was not about to put this theory to the test by giving my opponents more chances to crank on my knees. And so instead of working on leg locks, which I knew I was already proficient at, I started working on all the weaker areas of my game. Among other attacks, I started focusing greatly on brabo chokes, lat chokes, bread cutter chokes, wrap around chokes, carni’s (a shoulder lock from rubber guard named by Eddie Bravo), and other submissions which would not jeopardize my knees. I also transitioned some of my favorite leg lock attacks which I used to use from bottom guard and bottom half guard into sweeps. I would use the same entries for the leg locks as I would previously, but instead of finishing with a leg lock as I would before I learned to release the submission and sit up on top of my opponent to achieve the sweep. In turn, this resulted in my ending up on top in regular rolling more often than before, and subsequently my entire top game improved, including guard passing, half guard passing, maintaining mount, side mount and back mount and all of the submissions I’d been working on from top positions. Nor did I feel that my bottom guard game was any weaker than before, and despite my knees sometimes being sore after class and needing a little bit of icing, I saw that I could do every movement I had previously done in Jiu-Jitsu just as easily. Not only this, but my kicks and knees in muay thai felt as if they had more impact, my footwork felt faster and I actually think that my takedown defense in wrestling improved due to not only increased leg strength but increased core strength due to getting used to balancing on one leg as a part of physical therapy. And if we are to discuss tests of leg strength which fall outside the range of martial arts, just the other day I ran the fastest mile I’ve done in my life, at 6:28, running at 10 miles per hour for 3 minutes straight and just under that for the remainder. So now when I hear people say that “few people fully recover from ACL surgeries and return to martial arts” (and believe me, I have heard this quote frequently and said with one hundred percent sincerity), I can only shake my head at the limits that the human mind imposes on the body. I believe that few of the people who have quit martial arts as a result of ACL injuries have done it simply because of the injury itself but more because their minds were conditioned to believe they could not overcome it. Now that I have worked my way back through two ACL surgeries I believe even more in my ability to overcome other future obstacles and I fully realize the potential of injuries to make a martial artist better, both externally as well as internally.

Indeed, these past set backs should prepare me quite well for tomorrow morning, when I will undergo a minor surgery on my wrist to repair a partially torn ligament. I don’t yet know whether or not a subsequent surgery will be necessary after this one, and if it is I may be out from training for as much as 6 months and require titanium pins to hold the ligament in place, much like the ones I already have in my knees. Either way I certainly have at least a couple months of physical therapy to look forward to and yet I feel relatively un phased because I have been through it all before and worse with my ACL surgeries and the rehab they entailed. I am sure that even before it fully heals I will learn ways both in life and in the martial arts to work around this injury, and in fact, I already have. The words that I am typing right now are being done with only my left hand which should serve me well in achieving more dexterity in those digits and my Muay Thai training as of late has consisted almost entirely of kicks, knees and elbows which I feel has made me even better at those techniques. Now instead of dreading my return to martial arts I wonder what other new ways I can improve my arsenal through this injury, and if more are to come after that, as they quite likely will, I will do my best to count them as blessings instead of curses, and always return to the mat afterwards to see what new tricks I can develop out of these setbacks.

Though not injuries per say, there are a few notable martial artists who have become very accomplished not in spite of, but rather due to what most would call physical “handicaps” or “shortcomings”, but which I actually regard as advantages. For example, the world renowned Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu black belt and grappling champion Jean-Jacques Machado was born without a fully formed left hand. However, it is quite likely that he is better than he ever would have been had his hand formed fully before birth and has almost certainly developed any number of techniques which work well for him in competition as a direct result of this. Likewise, rising MMA fighter Nick Newell was born with only the upper half of his left arm and yet today he is undefeated at 10-0 and has one of the best guillotine chokes in the business which he very likely developed because of the difference of his anatomy. Finally, the greatly respected wrestler, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu practitioner and motivational speaker Kyle Maynard was born without either of his arms or legs, and yet he has been more successful in competition than most and continues to be an inspiration not only for grapplers and martial artists but people from all walks of life. In a recent online video Rener Gracie even had a public grappling session with Maynard and showed how he had developed a very unique technique for escaping bottom mount based entirely on his body type.

As can be seen, many physical “limitations” are only such in so far as they are mental blocks. Particularly in the martial arts, and most importantly the gentle art of Jiu-Jitsu, physical shortcomings can be turned into advantages if the mind of the practitioner is focused on overcoming adversity. Because injuries will inevitably happen to a martial artist the best thing he can do is to figure out how to turn them into positives instead of viewing them as negatives. If you are a martial artist, next time you have an injury try to use it as an opportunity to improve some other aspect of your game and once the injury has healed you may find that it was a blessing in disguise and that you are in fact better than you ever were before.

Jamey Bazes is a Poughkeepsie MMA practitioner holding a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu brown belt with over 15 years of competition experience earning over 100 tournament victories. He also holds a Masters of Arts Degree in English from SUNY New Paltz with a focus on the English Romantic poets.

Jamey Bazes is a Poughkeepsie MMA practitioner holding a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu brown belt with over 15 years of competition experience earning over 100 tournament victories. He also holds a Masters of Arts Degree in English from SUNY New Paltz with a focus on the English Romantic poets.

Hudson Valley MMA Ground n Pound

“Ground and pound”. To the lay person this phrase means little, but to the initiated fan of modern day Mixed Martial Arts this is a term which has become quite well known in recent years, much to the credit of color commentators for the Ultimate Fighting Championship like Joe Rogan and Mike Goldberg amongst others. But what exactly is “ground and pound”? Most MMA fans who have never trained with actual fighters or who only watch the sport casually will give answers that are not really satisfactory. The most common is that “ground and pound” is a style of striking an opponent on the ground in MMA, with the emphasis usually being on the methods used by the fighter in top position to strike the bottom fighter. While this statement is generally correct it does not truly do justice to the skill which many top fighters call their number one method for attaining victory. As anyone who has trained with a skilled Pro MMA fighter knows, “ground and pound” has every bit as many nuances as submission grappling, takedowns or stand up striking. Many people with limited training believe that there is little technique to striking on the ground and that once a fighter achieves a takedown he need only reign down punches or elbows until the referee steps in. However, “ground and pound” is a skill in itself and simply “swinging away” on a downed opponent with little regard to technique is a good way to get submitted or swept by an opponent with a good Jiu-Jitsu game. In this article I will outline four different “ground and pound” techniques which have been used by different fighters in high level MMA fights and explain what makes these techniques so effective.

There is no more fitting way to begin an article on the skill of ground-striking in MMA than to start with the man often quoted as “the godfather of Ground and Pound”, Mark “the Hammer” Coleman. Coleman began his MMA career back in 1996 at UFC 10, the early days of Mixed Martial Arts when the sport had yet to be regulated under the “Unified Rules”. Coming from a wrestling background and having been a former NCAA champion, the 6’1, 255lbs bruiser took to fighting like a fish to water. In those days Royce Gracie had already established the value of ground grappling and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu in MMA, and this is what truly paved the way for wrestlers, cluing them in to the fact that taking the opponent down and finishing them on the ground was a legitimate method for winning a contest. However, Royce had usually won his fights by using submission holds such as chokes and armlocks, rather than bludgeoning the opponent into defeat with punches, hammerfists, knees and elbows. Lacking the submission techniques available to BJJ artists but having every bit as much knowledge of ground positioning, Coleman was perhaps the first Mixed Martial Artist to routinely win fights simply by taking his opponents down and striking them until a referee either stepped in or they were rendered unconscious. Coleman had many methods for doing this, but one that I am going to look at in particular is what I will refer to as the “head in face” technique. This is one of the primary techniques which “The Hammer” used to win the most important fight in his career, his victory over Igor Vovchanchin in the “Pride Grand Prix 2000 finals” which led to his becoming the first ever Pride HW tournament champion. In essence this technique is quite simple, and yet devastatingly effective, and it is based on a few important principles that anyone must understand in order to recognize what makes for an effective “ground and pound” tactic. In this fight, Coleman made used of the “head in face technique” by standing in Igor’s full guard, then driving his forehead into his face and from there, punching in succession to the body, followed by single shots to the head.

Now, there are four important principles to ground and pound which one must understand if they are to separate a truly superior “gn’p” technique from simply striking a grounded opponent with reckless abandon. These principles are 1) controlling the arms 2) controlling the hips 3) controlling the head and 4) mixing up one’s strikes. Anyone who studies the art of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu knows that controlling the hips and the head make a grounded opponent nearly helpless, and this same principle applies to wrestling and “ground and pound”. If an opponent does not have free range of motion with his head then his hip movement is going to be very limited and likewise if he does not have full movement of his hips then his head movement will probably not amount to much. Let me explain more clearly. All bodily motion is dependent upon movement of the spine, which goes as far up as the back of the neck and base of the head, and as far down as the tailbone, which is parallel to the hips at the front of the body. The two points of the body where the spine provides its greatest function are at its top and bottom, in other words, the neck/head area, and the hip/lower back area. If a grappler controls one of these two points he has a good deal of control over his opponent. If he controls both his opponent’s mobility is practically null as he has isolated his spine at both of its key points and this will make strikes very difficult to defend against. This is essentially how control of hip and head movement makes for an effective “gnp” technique.

On the other hand, controlling an opponent’s arms is important because you take away his main tools of offense and most importantly, his greatest method of defense. Controlling one of your opponent’s arms is often enough to prevent him from escaping or countering most forms of “ground and pound”, while controlling both of them makes his ability to counter or escape even more difficult, granted of course that the aggressor has some sort of head or hip control.

Finally, mixing up strikes makes for an effective “ground and pound” tactic because the opponent never really knows what to expect. This means directing blows to different parts of the body, head and even limbs, as well as using different types of strikes such as hammerfists, downward elbows, diagonal elbows and straight and looping punches.

With Mark Coleman’s “head in face” attack on Igor Vovchanchin, he made good use of the first two and the fourth principles. He controlled Igor’s head very well, which in turn allowed him to control his hips, and he mixed up his strikes to the body and head. What Coleman did in this fight was to essentially stand up in Igor’s full guard and drive his head directly into Igor’s face, making his own head and neck a fifth point of contact with the ground so that he could base off of it and throw his punches with full power without sacrificing his balance. With his feet planted and his hips above his opponents’, the bottom man’s hips were also limited in their mobility. In this particular situation, since Igor could not free his head his spine and body as a whole were isolated and his guard rendered quite ineffective. The placement of Coleman’s forehead in Igor’s face provided two other special advantages, in that it limited Igor’s view of the strikes coming at him and also caused him quite a bit of discomfort. Coleman also directed his strikes to different areas, generally throwing several times to the body and once or twice to the head in succession. As such, Igor was less capable of guessing where the strikes would land next, and thus had a more difficult time defending. This is a technique which Coleman’s protégé Kevin Randleman would also later use with great success in his fighting career.

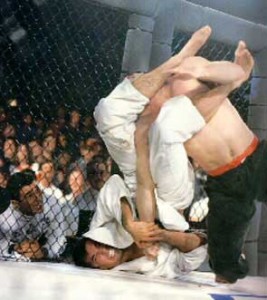

Rickson Gracie doing the gift wrap

However, an even more effective “ground and pound” tactic than Coleman’s “head in face technique” is the mounted “gift wrap” which the great Rickson Gracie used to defeat Masakatsu Funaki back in 2000. The Gracie family is well known for introducing Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu to the world, but their style of ground fighting is not only effective for submissions, it is also effective for striking as Rickson proved in this fight. Now it is important to note that the most significant aspect of Rickson’s “gift wrap” on Funaki is not the trapping of his arm, but rather, the mount position itself. When a grappler passes his opponents’ guard and is able to mount him he has complete control over his opponents’ hips because his entire body is positioned above them. As such, the opponent’s legs have been taken out of the equation and his upper body has been isolated. He does, however, still have movement of his head and the top portion of his spine, but as we will see Rickson’s technique later prevents this. In this fight, after weakening Funaki with some shots from mount, he grips Funaki’s right wrist with his right hand, while reaching under Funaki’s head with left arm. Following this, Rickson feeds Funaki’s right wrist to his own left hand which is underneath Masakatsu’s head. This results in Rickson being mounted on Funaki while the latter’s right arm is completely wrapped around his own head, leaving him with only one arm to defend against Rickson’s strikes. Not only is Funaki’s right arm now trapped, but his head is also held firmly in place by his own arm and his hips are being completely controlled by Rickson’s mount. Goals 1, 2 and 3 of our “gnp” outline have now been met, and Funaki has no way to defend himself since almost his entire body is being controlled. This is another outstanding “ground and pound” technique which works well for MMA.

The Mounted Crucifix

The third “ground and pound” position we will discuss has become quite popular in Mixed Martial Arts today and is generally referred to as “the side mounted crucifix”. This move has a number of variations and has been used very successfully by a number of fighters, most notably Jon Jones in his UFC Live 2 win over Vladimir Matyushenko and Roy Nelson in his win over Kimbo Slice on “The Ultimate Fighter” Season 10. Much like Rickson’s mounted “gift wrap”, the most important component of this technique is first having a dominant position, in this case side mount. Once sidemounted, the top opponent is past the bottom man’s hips much like a mounted opponent would be, except that in this case he has his weight distributed sidewise across his opponent’s chest and abdomen rather than being directly on top of him as he would be when mounted. From this position, both of the opponent’s arms are tied up with the top man having one arm free to punch or elbow his opponent’s head. This technique covers points 1, 2 and 3 of our “ground and pound” index. First, not only one but both of the opponent’s arms are trapped. Second, the hips are isolated in the sense that the guard has been passed and the legs cannot be used for much and the weight distribution of the top opponent makes hip movement difficult for the bottom man. Finally, with both shoulders and hips pinned to the mat and a large body across the bottom man’s chest, the defender’s head has fairly little mobility as well. The position can be made more effective by mixing up one’s strikes and Jones proved in his fight that it is possible to finish an opponent from here with elbows while Nelson proved in his that it is equally possible to dominate by punching with the free hand.

The final “ground and pound” position that I would like to discuss in this article is not usually recognized as such because it is done from a bottom position, but I would personally consider it every bit as valid as many done from top control and this is the “triangle position” from bottom guard. Most people see the triangle as a submission only due to its ability to cut off the blood to the brain, causing the opponent to either tap out or pass out. However, as Anderson Silva proved in his victory over Travis Lutter at UFC 67, this can also be a dominant position from which to land multiple short elbow strikes which in this case resulted in a submission not from the choke, but from the strikes being delivered. Generally, the term “ground and pound” seems to be reserved for striking techniques delivered by the top fighter to the bottom fighter, and the reason for this is most likely because strikes delivered from on top tend to have more weight and force behind them. Usually ending a fight with strikes from the bottom is difficult to do, unless, of course, it abides by enough of the 4 rules of our “ground and pound” index, like the triangle does. First, it is important to note that the guard position is the only bottom position capable of being considered dominant because the bottom man’s legs do partially shut off full movement of the top man’s hips. Because the bottom guard player has his ankles positioned above the hips of the top man, the top fighter cannot advance further to fully isolate the bottom man’s hips. This is the first key to why the triangle can be considered a dominant position despite being done from on bottom. The second reason is that one of the top opponent’s arms is taken out of the equation by the unique positioning of the bottom man, and the other arm is trapped across the bottom man’s chest, making it difficult for him to defend against strikes which was another key to successful “gn’p” that we mentioned. Finally, the most important aspect of why the “triangle position” is a dominant angle for “gnp” is because it exercises maximum head control. The top opponent’s head is being completely controlled by the legs and arms of the bottom man. As such, the top point of his spine is isolated and his mobility is greatly lessened. In the case of the Anderson/Lutter fight, Anderson had such a good triangle sunk in that he was able to deliver downward elbow strikes until the ref stepped in. As can be seen, if one thinks outside of the box and utilizes enough of the principles of the “ground and pound” index, it is possible to stop a fight with strikes even from a bottom position.

Clearly “ground and pound” techniques are not effective because of top position alone, they are dependent upon a number of principles being used effectively. The Mark Coleman/Igor Vovchanchin fight is an excellent example of how unique head control can be used to create enough pressure from top guard to threaten an opponent. The Rickson Gracie/Funaki fight is an example of how head and arm control can be obtained simultaneously from top mount leaving the opponent with no method of defense from strikes. Jones’ and Nelson’s “sidemounted crucifixes” are examples of how both arms of the bottom man can be trapped simultaneously leaving him vulnerable. Finally, the example of Anderson Silva’s triangle on Travis Lutter shows that if proper head control is utilized even a bottom position can give a fighter enough power to stop a fight with successive blows. Next time you watch MMA and you see strikes being thrown on the ground I suggest that you pay attention to which of the four points from our “ground and pound index” are being applied, and take note of what the aggressor could be doing to make his ground striking more effective. Knowledge of “ground and pound” techniques and the principles behind them will enhance your enjoyment as a Mixed Martial Arts’ viewer just as much as it can increase a fighter’s effectiveness in the ring.

Jamey Bazes is a Hudson Valley martial arts practitioner holding a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu brown belt with over 15 years of competition experience earning over 100 tournament victories. He also holds a Masters of Arts Degree in English from SUNY New Paltz with a focus on the English Romantic poets.